|

|

Joseph

Francis Alward

|

And

the LORD God said unto the serpent, Because thou hast done this, thou art

cursed above all cattle, and above every beast of the field; upon thy belly

shalt thou go, and dust shalt thou eat all the days of thy life (Genesis 3:14)

Traditionalists Believe the Serpent Had Legs

Some Bible skeptics, as well as most evangelical

fundamentalists, believe that the passage above means that the serpent had legs

with which to walk about the Garden of Eden before it tricked the woman, and

that afterward the Lord cursed the legs off the serpent.

Some of those who believe that the Genesis writer

thought the serpent had legs, then lost them in the curse, say that…well, the

Mesopotamians had serpents with legs in their myths, so the Genesis

writer is likely to have believed the same thing. Furthermore, Jews traditionally have believed that the Genesis

writer's serpent had legs before the curse, and who would better know what the

writer had in mind than the Jews? they argue.

Besides that, the serpent story doesn't make sense if the serpent didn’t

once have legs, according to them.

However, we cannot know for certain whether the

Genesis writer was aware of the Mesopotamian myths, and thus was influenced by

them, and the Hebrew's opinions are of no more consequence than the opinion of

anyone else, because they cannot have known what was in the mind of the Genesis

writer. Furthermore, it is not true

that the serpent story doesn't make sense if the serpent didn't have legs.

Perhaps the writer did

believe the serpent once had legs, but he easily could have believed that, say,

the serpent always went about on its belly, or he could have believed that the

serpent once got about upright without legs.

These scenarios are discussed more fully below.

The Genesis Writer Believed the Serpent Always Went

on Its Belly

The Genesis writer may have believed that the serpent

had been going about on its belly for the two days since it was created, and

that God perhaps might eventually have elevated it to the status of the other

beasts of the field by giving it legs, if only it hadn't tricked the

woman. The writer may have believed

that when the curse came, it had the force of causing the serpent to continue

to go about on its belly for all of the rest of the days of its life. It's like a blind man who could be cured by

God, but he commits a sin, and is then cursed by losing his chance to be cured

by God. The blind man was suffering

before the curse, just as the serpent was, but to have all hope for a cure

snatched away from him forever is surely a curse. So it could have been with the serpent, at least in the mind of

the Genesis writer.

There is another belief the Genesis writer might have

had which is more likely than the one I described above, in my opinion.

The Writer Believed the Serpent Held Itself Upright

without Legs

The writer may have believed the serpent moved

largely upright through the garden, holding itself vertical in much the same

manner as the King Cobra does, by using its coiled tail as a base on which it

may hold itself erect, and moved across the garden by means of a twisting

action of its coiled tail. After the

serpent tricked the woman, Yahweh took away its ability to hold itself erect,

and the serpent was condemned to spend the rest of its days going about on its

belly.

Once again, we see that there is a plausible

alternative belief the Genesis writer may have had which does not have the

serpent with legs before the curse.

And, again, it doesn't matter that Mesopotamian myths had serpents with

legs, or that Jews traditionally believed that the Genesis serpent had

legs. All that matters is what the

Bible says, and the Bible does not say that the serpent had legs before

the curse, and it does not say that the serpent had its legs removed in

the curse. Why, then, must we believe,

as some skeptics insists, that the Genesis writer's serpent had legs, if there

are plausible alternative explanations?

The notion that the Genesis writer believed that the

serpent had legs before the curse is certainly quite plausible, but it seems about

as likely that the Genesis writer thought the serpent twisted itself across the

garden in the manner I described in the second alternative above, and therefore

the serpent need not have had legs.

Readers

who still doubt that the Genesis writer could have had any other type of

serpent in mind besides one with legs, let them read further.

The Writer Believed It Was A Winged, Legless Serpent

The Genesis author doesn't say that the serpent had legs

before the curse, nor does he say that Yahweh removed the legs when he cursed

the serpent, and the writer doesn't say how the serpent moved about the garden,

so we are free to imagine any mythically plausible form of locomotion beside

walking, as long as it's consistent with the myth.

Those who argue that the Genesis writer's mythical

serpent had legs naturally claim that the serpent got about the garden on its

legs, but there's no textual evidence to support this. Perhaps, then, the serpent was legless and flew

about the Garden of Eden. Such a beast,

for example, is found in the myths of the ancient Aztecs, who worshipped a

winged, legless serpent called Quetzalcoatl.

More importantly, a winged, legless serpent is found in the mythology of

the ancient Arabia; the legless flying serpent in Arabian mythology was said to

have been the guardian of a tree1, just like the serpent in the

Genesis story. The fact that both

serpents guarded trees suggests that the serpents in both myths may have been

based on a common antecedent now lost to history that predated each of them. If this is the first occurrence of a

biblical myth based on a lost antecedent, it is certainly not the last one. Some parallel gospel stories from

Luke and Matthew are believed to have originated from a common source, now

lost, called Q (stands for Quelle, German for "source").

If two or more gospels stories can have a common, but lost, antecedent,

then so could two or more serpent myths have had a common source, now lost.

We are thus

left with what seems to be a quite plausible alternative view of the Genesis

writer's serpent. Just as we are free

to imagine that the Genesis writer's serpent had legs before the  curse, and lost them in the curse, even though

there's no biblical evidence to support the notion that the serpent had legs,

we are equally free to imagine that the writer had in mind an amphiptere, a winged, legless serpent

that lost its wings in the curse, and was consigned all the rest of the days of

its life to go about on its belly.

curse, and lost them in the curse, even though

there's no biblical evidence to support the notion that the serpent had legs,

we are equally free to imagine that the writer had in mind an amphiptere, a winged, legless serpent

that lost its wings in the curse, and was consigned all the rest of the days of

its life to go about on its belly.

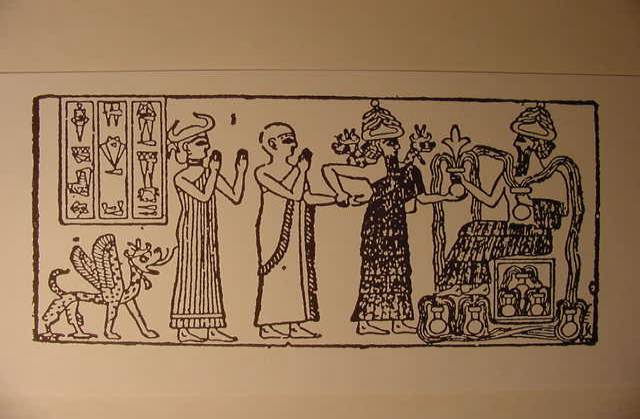

The picture at the top right is an artist's

conception of a winged, legless serpent.

At bottom left is an ancient depiction of a winged serpent.

Some Bible skeptics insist that the suggestion that

the serpent in the Genesis myth might have had wings is too unbelievable, even

"stupid," so perhaps it would be worth the time to point out that one

of the most revered biblical skeptics of all time, Robert Green Ingersoll,

seemed not to reject this notion. In recognition of his sublime contributions

to the field of biblical skepticism, the Council for Secular Humanism created the Robert

Some Bible skeptics insist that the suggestion that

the serpent in the Genesis myth might have had wings is too unbelievable, even

"stupid," so perhaps it would be worth the time to point out that one

of the most revered biblical skeptics of all time, Robert Green Ingersoll,

seemed not to reject this notion. In recognition of his sublime contributions

to the field of biblical skepticism, the Council for Secular Humanism created the Robert

Green Ingersoll Memorial Committee, which is dedicated to preserving the memory and works of this

19th Century orator. Ingersoll's

lectures are also featured prominently as The Complete

Works Of Ingersoll on The Secular Web.

Excerpted below from "The Works of Robert G.

Ingersoll," Volume II Lectures (1900), is the observation in his lecture, The Fall2, that Dr. Matthew Henry, 1662-1714, English minister

and Bible commentator, allows for the possibility that the devil serpent was a

flying serpent:

Excerpted below from "The Works of Robert G.

Ingersoll," Volume II Lectures (1900), is the observation in his lecture, The Fall2, that Dr. Matthew Henry, 1662-1714, English minister

and Bible commentator, allows for the possibility that the devil serpent was a

flying serpent:

Dr.

Henry…insists that "it is certain that the devil that beguiled Eve is the

old serpent… who attacked our first parents was surely the prince of devils…

Perhaps it was a flying serpent which seemed to come from on

high." (Emphasis added)

There is no statement by Ingersoll that he rejects

outright this notion, nor is there any comment by him which would suggest that

he thought Dr. Henry was misguided. If

Ingersoll and Matthew Henry could accept the notion of the garden serpent being

a flying serpent, then what do skeptics who deny this possibility know that

they didn't? For addition reasons to believe that the Garden serpent may have

been winged, but legless, the reader should read the "Genesis Serpent Was

Variation on Sumerian Serpent " section, below.

Genesis Serpent Was Variation on Sumerian Serpent

In

"The

Garden of Eden Myth", Walter Mattfield writes

[B]

behind all myths are historical kernels. In this case the "kernels"

are vestiges of earlier Mesopotamian4 myths reaching back to the 3rd

and 2nd milleniums BCE which the Hebrews later reinterpreted into the Garden of

Eden and its motifs.

My

research has concluded that the Sumerian Dragon-Serpent called

"Nin-Gish-Zida" is what lies behind the Genesis Myth….It

is my understanding that the serpent in the garden of Eden is drawing from this

Sumerian motif. The illustration is from a cylinder seal of Gudaea of Lagash5,

ca. 2100 BCE. (The winged, four-legged

serpent is on the left in the photograph below, taken from the website at http://www.bibleorigins.net/Serpentningishzida.html)

The

Genesis writer gives no clue to how the serpent got about the Garden, so if

it's true that the writer's serpent was the Sumerian one on the seal above, or

some twist or variation on that serpent, then we are free to imagine any one of

the apparently equally likely serpents:

1. The serpent had legs and wings.

2. The serpent had legs, but no wings.

3. The serpent had wings, but no legs.

Consider

the first possibility: If we are to

imagine that the writer's serpent had legs and wings, then in order for

Yahweh's curse to have made sense, the writer would have had to have imagined

that Yahweh cursed off not only the serpent's legs, but also its wings. Thus, the writer would have left off two

important facts about Yahweh's curse:

That the serpent had legs, then lost them, and that the serpent had

wings, and lost them, too.

What

would seem more likely is that the writer imagined only that the Genesis

serpent had one, or the other, of the two types of of locomotion, and that he

didn't tell us about this one attribute, rather than he didn't tell us

about the two attributes. This

leaves us with one or the other of the two remaining scenarios: Either the writer's serpent was a variation

of the mythical Sumerian serpent with legs, but without wings, or else it was

the Sumerian serpent with wings, but no legs.

Thus,

we see once again that there is a plausible alternative to the belief that the

Genesis writer's serpent had to have had legs.

Note

that the serpent on the ancient seal has wings, as well as legs. If one wanted to argue that the Genesis

writer removed the Sumerian serpent's wings, but left the legs, another could

equally well argue that the Genesis writer removed the legs, but left the

wings. Either

way, the curse put on the serpent by Yahweh because it tricked the woman in the

Garden makes sense. Either Yahweh

cursed off the legs of the wingless serpent, or else Yahweh cursed off the

wings of the legless serpent.

Skeptics who insist the Genesis writer must have had

in mind a serpent with legs modeled after the serpent of Sumerian mythology

need to explain what happened to the Sumerian serpent's wings when it arrived

in the mind of the Genesis writer, and then explain how they can be so sure

that the Genesis writer could not have had in mind a serpent that got about the

Garden with wings, and lost those wings in Yahweh's curse.

Footnotes

1. The amphiptere, a winged, legless serpent, was the guardian

of the frankincense tree in Arabian mythology

2. "The Fall":

http://www.sacred-texts.com/aor/ing/vol02/i0113.htm

3. Blue Letter

Bible: http://www.blueletterbible.org/

4. Mesopotamia was an ancient region of southwest Asia between the Tigris

and Euphrates rivers in modern-day Iraq. Probably settled before 5000 B.C., the area was the home of numerous early

civilizations, including Sumer, Akkad, Babylonia, and Assyria. Source:

Source: The

American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition

Copyright © 2000 by Houghton Mifflin Company.

Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.)

5. Lagash is the name of a

Sumerian city-state located by the Tigris River, in southeast Mesopotamia. The

first cities were developed in the Mesopotamian plain, specifically in the

south at about 3500 – 2800 BCE. The

ruler of Lagash was Gudea. Ref: "Lagash" http://www.mnsu.edu/emuseum/archaeology/sites/middle_east/lagash.html)